In breach of the contract he signed, Charles Chang unilaterally takes paintings but refuses to provide the duly required proof of purchase, pay the transfer fee or cooperate with the artist.

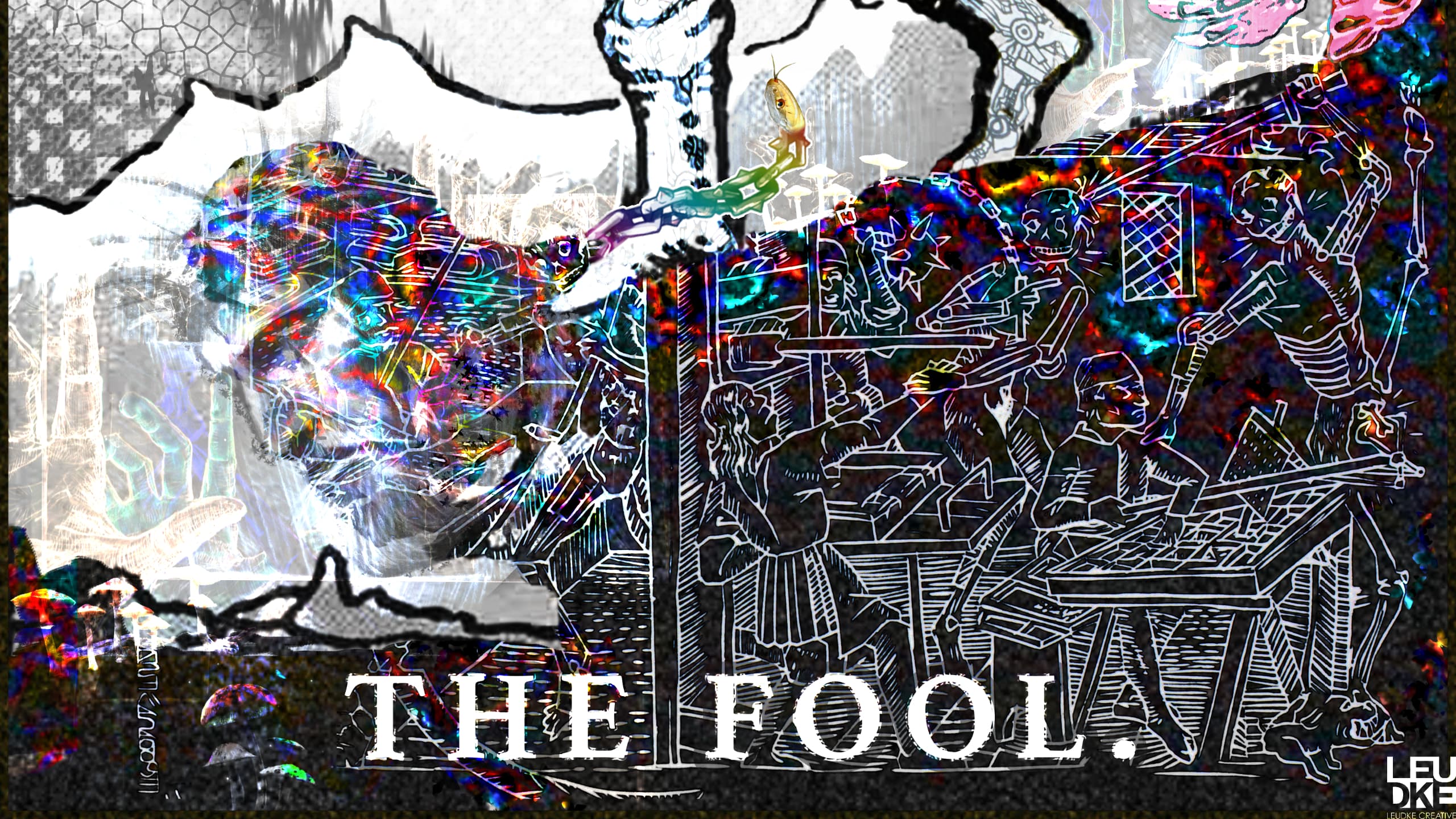

Artist's Statement:

In breach of the contract he signed…

Charles Chang unilaterally takes paintings but refuses to provide the duly required proof of purchase, pay the transfer fee or cooperate with the artist.

I bought the paintings through Vega. When I left, I paid for the paintings as a fair way to settle things. I am not in the business of art and this transfer is to/ from related parties so I don't think it requires you to be paid for it. You so quickly turn this into a legal issue with me? I am disappointed you took this path. I am no longer willing to help you.

—Charles Chang

Lyra Growth Partners, President & Founder (2015-)

Vega / Sequel Naturals President & Founder (2001-2015)

LinkedIn: Charles Chang

Our founder Charles is a serial entrepreneur who started Lyra Growth Partners in 2015. He is actively involved in the investment process, working with our investee companies, and supporting our founders.

Prior to Lyra, Charles was founder and President of Vega, which he started from scratch from his basement in 2004. Financed by his life savings, a second mortgage on his house and credit cards, Charles led Vega to become a leading brand of clean, plant–based nutritional products in North America.

Honouring a triple bottom line approach to business and recognizing people are the greatest source of sustainable competitive advantage, Vega and Charles have received many accolades, including: Fastest Growing Companies, Best Workplace, Best Managed Companies and Entrepreneur of the Year. In 2015, Charles led the sale of Vega to White Wave Foods (NYSE: WWAV) for US$550 million.

In 2016, Charles helped establish the Charles Chang Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship at Simon Fraser University, an interdisciplinary home and academic hub where people and ideas converge to foster entrepreneurial thinking and action.

Charles is also co-founder of PowerPlay Young Entrepreneurs, a non-profit organization that helps elementary school students develop an entrepreneurial mindset. Using real-world, hands-on learning experiences, PowerPlay helps build confidence and resiliency and develop practical life skills.

Charles lives with his family in West Vancouver, BC and is an active member of Young Presidents Organization (YPO), an avid golfer, fly fisherman, mountain biker, skier and Whistlerite wannabe.

Any views or opinions presented in this artwork are solely those of the artist and might not represent those of Leudke Creative, Sequel Naturals, Lyra or Charles Chang